Communication, Knowledge, Bodies and God

Why is communication so difficult?

Sometimes I will talk to somebody, and think that I’m expressing myself really clearly when I’m not. I seem to make perfect sense. Yet when I hear what the other person says in response, it is obvious that they heard something quite different from what I thought I said. What seemed so clear and easily understandable to me, is apparently quite opaque to the other person.

It happens all the time, and not just to me. For example, I frequently observe Christians having an argument over some point of doctrine. One person puts forward an idea X. The other person actually agrees with X but is concerned about the consequences of taking idea X too far, so they explain some of the flaws with X. Now, the first person is fully aware of the flaws of idea X, but they still think it’s a good idea, so they reiterate the good points about X. To the second person, it sounds like the first person didn’t understand the dire consequences of taking X too far, so they restate their understanding of X’s flaws. And so on and so forth. Both of them agree that X is a good idea but shouldn’t be taken too far. Yet a heated argument ensues. Over nothing.

We make assumptions about things that cause us no end of trouble. It happens with married couples all the time. For example, Eleanor asks her husband Edward to put the washing out on the line. Edward goes and hangs out the washing thinking what a good husband he is for helping Eleanor out. He hangs out the washing with great care because he knows Eleanor is rather particular about the washing. Each shirt is pegged precisely 2 cm away from the next garment. Every sock is folded exactly half-way along its length. He even plans his garment placement so that the weight is evenly distributed around clothesline, thus preserving its structural integrity. He fully expects Eleanor to beam with pleasure at his obvious care and consideration. And yet, when Eleanor comes out to view his handiwork, she is horrified. Why? Because Edward pegged all the shirts to the line instead of hanging them from coat-hangers.

How could Edward not know that shirts go on hangers? Hanging them on the line leaves a crease and peg marks that Eleanor has to iron out, adding to the mountain of work she already has to do. She had even put the hangers very obviously next to the peg bucket before he started. Why on earth would she put them there, if not for hanging the shirts? It’s just so obvious. Does he not think? And so poor Edward is crushed and resolves never to help with the housework again. Eleanor consequently becomes convinced that Edward is both lazy and mentally deficient.

All these kinds of problems occur, even when people grow up speaking the same language, living in the same culture, walking around similar places. It becomes even more complicated when people speak different languages and come from different cultures. Sometimes I wonder that we ever manage to communicate at all.

The embodied mind and subjectivity

Looking at things from a cognitive perspective, we can see that all our knowledge is situated and contextual. Whenever I learn something, I learn it in a particular place, at a particular time, when I am in a particular emotional state. For example, when I was in Year 11 at school, I learned Newton’s Equations of Motion:

v2 = u2 + 2as

s = ut + ½at2

Don’t worry if they mean nothing to you. It’s not important. My point is that thousands (probably millions) of other people have learned those same equations, just like me. Those equations are the same, no matter who learns them, but… nobody else learned those equations in the same context that I did. Nobody sat in the same chair in the same classroom at the same school that I did. Yet, when I think about the equations of motion, I always remember that school, that classroom, and my Physics teacher. I also remember when I learned the calculus behind them in my maths class, and later at university. My understanding of the equations of motion will always be coloured and shaped by the context in which I learned them. The strange outcome of this, is that it is entirely possible for us to dislike abstract concepts. For example, if I disliked my Physics teacher and found the equations difficult to understand, then I may come to actually dislike Newton’s equations of motion. I can form a negative preference toward a mathematical description of the way objects move in a vacuum. The equations are not in any way affected by my disregard for them. They don’t care if I think they’re stupid, because they don’t really exist. They are just a bunch of symbols that have an agreed meaning amongst a smallish group of educated human beings. Is that not strange?

Why is it that we can feel emotions about abstract things like mathematical equations? In their book, Philosophy in the Flesh, Lakoff and Johnson 1 write that all our knowledge and understanding is shaped by the fact that we have bodies. We never learn anything in abstract. We learn things at a certain point in time, feeling a certain way, in a certain location. We learn things in a body. Even the way we think and reason is shaped by the fact that we have eyes, hands, ears and hormones that run through our bloodstream.

This means that there is no such thing as a disembodied, objective human mind that is free from emotional attachment or irrationality. We can never have a completely emotionless, disembodied, objective view of anything. Everything is subjective.

Does this mean, then, that we are doomed to float in a sea of meaningless relativism, unable to know anything or communicate with anyone? Obviously not, or there would be no point to you reading this. We somehow manage to know things and communicate with others, however imperfectly. We can do this, because we all have a few things in common that make communication and shared understanding possible.

I mean to come back to this later, but the point is that we can communicate because we all share the experience of having brains and bodies. Unfortunately, we don’t share our brains or bodies with anyone else. My brain and my body is different from your brain and your body. Our experiences are entirely different too. Although we may have a few general things in common like school, television, driving in cars, etc. we probably didn’t go to the same school, watch the same television, or drive in the same cars. So, I can never communicate an exact imprint of what I know to you, because when I talk about schools, cars and televisions, my words evoke different experiences from the ones you had.

Categorisation

We have trouble communicating because we can’t get into each other’s bodies and experience things as somebody else does. But that is just the beginning of the problem. Categorisation makes the problem even more complex.

Categorisation is the most fundamental building block of knowing anything. As Lakoff and Johnson write:

Every living being categorizes. Even the amoeba categorizes the things it encounters into food or nonfood, what it moves toward or moves away from. The amoeba cannot choose whether to categorize; it just does. The same is true at every level of the animal world. Animals categorize food, predators, possible mates, members of their own species, and so on. How animals categorize depends on their sensing apparatus and their ability to move themselves and to manipulate objects. 2

Categorisation is essential to almost everything we do. Information from our eyes is categorised into objects so we see a tree, grass, a person, etc., instead of a mass of coloured dots. This allows us to quickly process a scene, looking for important things like danger, food or other people. We also learn by categorisation. We learn, for instance, that certain objects are good for holding liquids and drinking out of. When we recognise similar objects later, we then know that we can drink out of them; saving us the trouble of performing trial-and-error experiments.

Unfortunately, this learning aspect is yet another mechanism that makes communication difficult. Our knowledge about categories is continually being updated and refined as we interact with the world. This causes problems for anyone trying to study categorisations at the very basic level, because the very experiments set up to investigate categorisation cause us to change and update our categories 3. It also causes problems when I try to communicate. For example, what I mean by the phrase ‘politically correct’ today may not be the same as what I meant when I used the term two weeks ago. In the meantime, I may have been to a seminar on diplomatic use of language and thus gained a more subtle understanding of the phrase. On the other hand, I may have heard a politician use a particularly amusing euphemism and that also changes my category. These shifts and changes in categories mean that not only does understanding vary greatly between individuals, but even in the same person.

Our categories are also highly contextual. That is, when we categorise things, we don’t just store information in our brains about which things belong in a group, but also the contexts in which the category is meaningful. We do this automatically and unconsciously. Homonyms are a good example—where one word has several meanings. For instance, the word cake refers to ‘a baked mass of bread or substance of similar kind, distinguished from a loaf or other ordinary bread, either by its form or by its composition’.4 However, in the context of alternative music, Cake refers to the name of a band. In the context of a political discussion, the phrase ‘everyone wants a slice of the cake’ refers to a resource to be shared out. We work out the meaning from the context. And when we communicate, we often leave out a lot of contextual information because we are in the context. When somebody else comes along, however, the context may not be immediately apparent.

The upshot of all this is that categories don’t just vary between different people, they vary within the same person. Categories change over time and are arranged differently to suit different contexts. This makes it difficult to communicate because even if I talk about a concert we experienced together last week, our individual understandings of it may have changed in the meantime. In addition, I might also imagine that you immediately understand I mean last week’s concert. You, on the other hand, may have been thinking about a concert next week because you had just been in the process of buying tickets. Our highly-adaptive brains make communication just that much harder. This is just the beginning of our problems however.

Categorisation and language

Our difficulties in communicating with each other are further exacerbated by the complexities of language. People used to think that categorising and choosing a word to describe a category were pretty much the same thing. That is, by naming something we categorise it together with everything else of that name. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The relationship between categorisation and words is much more complicated 5.

The problem comes from the fact that naming and language are tools for communication, not necessarily for categorisation. The two are, of course, closely linked, but they are different. Categorisation groups similar things together so that our brains can save some effort in processing the masses of sensory input they constantly receive. Communication, on the other hand, is about sharing an understanding (at least, that will do as a working definition). This means that when I am communicating with somebody, I will choose words that I think they will understand. If I use words that the other person does not understand, then communication will fail.

Most languages contain at least a few synonymous words. To represent any particular concept I can usually think of multiple ways to phrase the idea. This is particularly evident in the English language. “English retains probably the richest vocabulary, and most diverse shading of meaning, of any language…No other language has so many words all saying the same thing” 6. So, when I communicate, I will ideally try and phrase things in a way that I think you will understand.

The potential for problems here is enormous. When I speak to you, something rather complicated is going on:

- I know something

- I attempt to translate from my category structure to words I think you will understand

- You hear what I say

- You map the words I use onto your own category structure.

And, of course, I can only guess (perhaps very well, perhaps not) at what you will or will not understand. I do not know exactly what category structures my words will evoke in your mind. When I use the word ‘bird’, for example, I may not know what kinds of birds you have experienced. If you have only ever seen penguins, then your understanding of ‘bird’ will differ from mine.

Often we try and get around this by introducing redundancies. We say the same thing a number of different ways in the hope that our intended meaning will become clearer. That is why we have so many similes–each one with slightly different shades of meaning. Repeating ourselves certainly can help, but it can also introduce more potential for miscommunication, since the process is repeated all over again.

Unfortunately for our attempts to communicate, this means that language is always one step removed from what we know. And it is this kind of idea that gives rise to street-level ideas of post-modernism. That is, when we read or hear something, we can never fully grasp what the author or speaker really means. All we can do is take their words and interpret them according to our own understanding. This leads one to ask the question ‘Does it really matter then, what the author intended, since people will interpret things their own way anyhow?’ Given the plethora of homonyms, synonyms and colloquialisms in most languages, it is entirely possible to construct a meaning completely different from what the author intended (not that we can ever know what the author intended anyhow).

If all our understanding arises from context, environment and culture, then changing context, environment or culture changes understanding. What I understand as true and obvious may be completely different to someone who has grown up in a different culture and environment; especially if they speak a different language. One could be forgiven for reaching the conclusion that words are essentially arbitrary constructions that the listener manipulates to suit their own understanding of the world, regardless of what they hear.

I would argue, however, that not all of our understanding arises from culture and environment. Nor is knowledge restricted to arrangements of words. Not everything is relative. I will address this later. For the moment, we see that language has a complex relationship with knowledge, which adds to our difficulties in communicating.

Categorisation and social relations

There is yet another layer of complexity to communication and knowledge. I said earlier that categorisation is the fundamental building block of knowing anything. This includes ourselves and other people. We categorise other people (unconsciously and automatically) into groups, and this determines how we expect them to act, and how we act towards them. Further, we also categorise ourselves as being part of various groups. This is a central theme of social psychology.

How we categorise other people, and how we categorise ourselves, changes the way we understand the world. McGarty 7 uses the example of a football match to illustrate this:

Imagine you are going to watch a football match at a stadium between a team you support and a traditional rival. In order to understand the game you would, at the very least, need to categorize the players as belonging to different teams. To avoid being arrested you would need to categorize yourself as a spectator and not as a player. These categorizations are relatively obvious and may require little if any conscious thought on your part. More interestingly, however, you may come to categorize yourself as a supporter of one of the teams.

If you are like most supporters, as incidents occur on the field you will come to classify decisions by the referee or umpire as fair or unfair (and hence to be met with silence or derision) and segments of play as worthy of comment, applause or silence. You may well notice that many of your classifications seem to shared by other people who support the same team as you.

However, you could also hardly fail to notice that the classifications that you share with other supporters of your team seem to be keenly contested by the opposition supporters. They seem to classify fair decisions as worthy of derision and often greet examples of the most scintillating play with stony silence. However, rather than being puzzled by this disagreement we actually expect this perverse behaviour from the opposition.

We create social identities based on how we categorise ourselves, and how we categorise others. This allows us to predict how people will behave, as with the opposition supporters in the football example. This in turn allows us to describe peoples’ behaviour as ‘strange’ or ‘unusual’ if they do not behave in the way we expect. It also allows us to know what behaviour to expect of ourselves. For example, if I identify myself as a male, this has significant implications for which toilet I use in public buildings.

The process of categorising other people is called stereotyping. In modern usage, this tends to have negative connotations, alluding to racism or discrimination. And certainly, stereotyping is the mental mechanism that allows racism and discrimination. However, in the context of cognitive science, stereotyping refers simply to categorising people, not to the inferences we draw from our stereotypes.

However, racism and discrimination serve to demonstrate the profound power embedded in how we categorise ourselves and each other. Bowker and Star8 explore this in great detail, looking at examples including race categorisations under Apartheid and the classification of tuberculosis patients. Other examples include whether someone is categorised as ‘homosexual’, or ‘disabled’, or an ‘academic’, or a ‘professional’. Even seemingly simple categories such as ‘alive’ or ‘dead’ and ‘male’ or ‘female’ can have profound consequences for how we treat people.

In the context of communication and knowledge, this has particular relevance when we consider our ability to evaluate information. Human beings have the ability to both mistakenly believe something, and to deceive others. We also have the ability to evaluate information and make decisions about whether we accept or reject it as true. The way we categorise a particular speaker (or text) has a significant impact on how we evaluate what they say. Categorising someone as a ‘scientist’, ‘mentally ill’, or a ‘con man’ implies certain assumptions about the reliability of what they say.

This goes beyond simply understanding what somebody else wishes to communicate. This brings in questions of expertise and motivation. Categorising someone as a ‘scientist’ implies that they have authority to speak about their particular area of research. Categorising somebody as a ‘con man’ implies that he may try to deceive me because he is motivated by a desire to get my money. My understanding of a person’s expertise and motivation has a significant impact on how I evaluate what they say.

My self-perception also has a significant impact on how I evaluate an idea. Imagine for a moment that I am a nuclear physicist in discussion with a ten-year-old child. If that child tells me that atoms are made of (very) small fish that like to kiss each other, this may well conflict with my understanding of atomic structure. I am likely to evaluate the claim based on:

- Whether the claim fits with my understanding of atomic structure;

- My estimation of the child’s expertise and motivation; and,

- My estimation of my own expertise.

Since I consider myself (a nuclear physicist) an expert in atomic structure, it is most likely that I would reject the small fish claim. If the situation were reversed, and a nuclear physicist told me, a ten-year-old child, that atoms were made of small fish, then my decision to accept or reject the idea would likely be very different.

So we now have two layers to the communication problem:

- The problem of understanding. Because our experiences are subjective and tied to our bodies, I can never completely understand what another person wishes to communicate. The categories they invoke in my mind may be similar to the categories in their own, however, their category structures will have been formed by experiences entirely different to mine. Furthermore, the structure of the categories in both our minds changes as we experience the world. This introduces even further sources of variation in our understanding.

- The problem of evaluation. In addition to understanding what someone is trying to communicate, there is also the problem of evaluating the truth of their understanding. It is entirely possible that a person talking to me has a mistaken understanding. It is also possible that they are trying to deceive me. So, I am required to make a decision as to whether I accept or reject the authority of the person communicating with me. There are no guarantees as to whether my decision will reflect reality.

In the next section we will examine why communication is possible, in spite of the problem of understanding. The second problem, that of evaluation, I will leave for the philosophers to discuss, since it is outside my area of expertise.

Embodied Foundations of Knowledge

So are we doomed to complete subjectivity? The basis of our understanding anything is through the category structures and cognitive models in our minds. These are not hard-wired, but based entirely on our experience of the world through a body. Our experience of the world varies hugely across various cultures, languages and geographies. Not even our bodies are the same, but male differs from female and our bodies have larger or smaller bits, and some of us even have bits missing. How can we ever hope to understand anything another person communicates?

Conceptual metaphors

In spite of the variations in our experiences, we all have two things in common.

Firstly, we all have a brain (more or less). If we don’t have a brain then we die. Our brains are quite similar too. Most of us have a cerebral cortex, limbic system, cerebellum etc. and they all have fairly specific roles. The basic architecture is much the same for everyone. This means that our brains work in quite similar ways.

Secondly, we all have a body (more or less). Our bodies may not all have the same bits, but we all have some sort of body. Again, if we don’t have one, we die. Our bodies all come from a roughly similar blue-print, even if there are infinite variations. Having two legs, two arms, a face and hands is fairly common amongst human beings. And having these various appendages shapes the way our brains function because all the input a brain receives, it receives from the body. These commonalities mean that we all have a few basic concepts that are pretty much the same for everybody. For example, because the vast majority of us have eyes on only one side of our body, we have a concept of back and front. The structure of our eyes, arms and legs means that we are much more easily able to interact with things in front of us. Thus, if I talk about something being in front of me, then you have a pretty good idea of where it is, because we have a common concept of what front means.

There are quite a number of fairly basic categories and concepts that are common to nearly everybody. Because we have a body which can move, and can move other things, we all have a few basic spatial-relation concepts9. Another example is in/out. I can walk into a building; or out of a village; or into a garden; or out of a bathroom. Yet another example is paths, roads and passages. Almost all of us move between areas where there is food, areas where we sleep, and areas where we do other things. To get from one place to another I will follow some sort of route. This is another reasonably common concept. 10

Interestingly though, we also project these bodily concepts to other things. For example, we don’t just think of people as having fronts and backs. We also attribute fronts and backs to objects like animals, cars, houses and televisions. Animals have eyes, so we attribute them with a front. Buildings often have a main entrance, so we call that side of the building the front.

We even use front and back concepts for things with no front/backdefining features. For example, we say things like ‘I’m in front of the tree’, or ‘she was behind the rock’. The tree or rock only has a front or back in relation to where I am standing. But since we are used to ‘facing’ other human beings, we can talk (and think) as if trees or rocks also had fronts or backs and they are facing us.

We also make metaphorical mappings from bodily concepts to abstract concepts. For example, we commonly talk about emotional states as if they were bounded regions of space. I might say ‘I’m coming out of a depression’, or ’He’s not in a good state’. These mappings are not just linguistic conventions—they are basic building blocks of how we think. We know that emotional states are not really physical locations, but we have no other way of thinking about abstract concepts, except in terms of things we have already experienced.

These projections of bodily concepts onto other things are called conceptual metaphors11. These metaphors form the building blocks of most of our reasoning. We build cognitive models of how the world works based on a number of primary metaphors that we learn from a very young age. Primary metaphors are used to build complex metaphors, providing us with mental models of how things work.

The possibility of communication

Communication is possible, even though different people may have very different conceptual systems. It is just difficult.

The way people think varies greatly between cultures because there are many ways to form a conceptual mapping from bodily experience to abstract concept. For example, in English, when I say ‘The elephant is in front of the tree’, I mean that the elephant is between the tree and myself. In the Hasua language, saying the Elephant is in front on the tree would mean the opposite: That the elephant was on the other side of the tree12. In Hasua, ‘front’ means facing the same direction I am. Both are valid ways of conceptualising orientation.

In spite of this, even though the mapping from bodily concept to abstract concept is largely influenced by culture and environment, bodily concepts remain much the same. Also, because we have common needs for things like food, clothing and shelter, many other basic experiences are the same regardless of culture and environment.

Within my own culture, surrounded by people who have enormous amounts of similar experiences to me, and share similar conceptual systems, communication is relatively easy. Problems still arise, for example, I might assume someone has experienced something in common with me, when they have not. And there are always slight variations in our experiences. On the whole, however, our conceptual systems are fairly similar and it is possible to make sense of each other.

Across cultures and languages, the task is much more difficult, but still possible because of universal bodily experiences. Even if someone’s conceptual system is radically different from my own, it is still possible for me to understand another person’s way of thinking. Our brains are flexible enough to learn new conceptual metaphors. We can even think about the same concept using multiple, mutually inconsistent metaphors. So it is possible for us to learn to see things differently.

Communication is possible. Certainly, some things will be impossible for me to understand until I have experienced them and lived in the culture. There will always be some concepts however, like spatialrelations, that I can learn because I have a body, just like everyone else. So then, communication is possible, but it is difficult and will never be a perfect transfer from mind to mind.

Implications for theology

What are the implications of this understanding of knowledge and communication? In their books, Lackoff and Johnson13,14,15,16 draw some far-reaching conclusions for philosophy, politics and ‘morality’. The things I discuss here are really just the tip of the iceberg. I will begin with some of the conclusions that Lackoff and Johnson draw themselves, then move on to some of my own thoughts on embodied knowledge and theology.

Lackoff and Johnson on ‘morality’

What do Lakoff and Johnson think about God? While they detail at length how their research and understanding challenges modern philosophy on many different fronts, they are largely silent about religion. I can only speculate as to why this is. Perhaps they wish to avoid treading on others’ personal treasured beliefs—although they seem to have no qualms about suggesting the basis for much philosophical reasoning is flawed. Perhaps they simply operate with an implicit assumption that there is no God, and thus they do not need to say anything about it. I don’t know.

Lakoff and Johnson do have a lot to say about morality, however. In Moral Politics, Lakoff argues that all of American politics is based around morality, and most moral reasoning centres around conceptions of the ideal family. This, he argues, explains why the conservative right and liberal left cannot understand each other; they conceptualise morality in completely different ways. It is an interesting read, but American politics is slightly outside the sphere of my discussion here.

In Philosophy in the Flesh, Lakoff and Johnson devote a whole chapter to ‘Morality’. They analyse the metaphorical bases for moral reasoning and thinking, then show how these metaphors are tied together by conceptions of what the ideal family is like. They propose two ‘ideal’ models, one called the ‘Strict Father’ model, and the other the ‘Nurturant Parent’ model. In Moral Politics Lakoff equates the strict father model with conservative (right wing) politics, and the nurturant parent model with liberal (left wing) politics. In Philosophy in the Flesh, Lakoff and Johnson extend this to ‘Christian Ethics’. This is what they have to say:

In monotheistic religions, […] the moral authority is God the Father Almighty, creator and sustainer of all that is and source of all that is good. On the Strict Father interpretation, God is the stern and unforgiving lawgiver who rewards the righteous and punishes wrongdoers. The key to living morally is to hear God’s commandments and to align one’s will with God’s will. This requires great moral strength, because one has to overcome the assaults of the Devil and the temptations of the flesh.

When God is conceived as Nurturant Parent (sometimes as Mother), he is the all-loving, all-merciful protector and nurturer of his people. God is Love, and, in the Christian tradition, Jesus is the bearer of that nurturant and sacrificing love for all humankind. Although there is a place for moral law (“Think not that I come to abolish the law and the prophets; I come not to abolish but to fulfill,” Matthew 5:17), moral commandment and law are not the central focus. Instead, morality is about developing “purity of heart” so that, through empathy, we will reach out to others in acts of love. 17

This, in and of itself, is relatively harmless. We all know that there are conservative types of Christians, and liberal types of Christians, just like there are conservative and liberal politicians. Most of us also know that going to one extreme or the other misses the point of Christianity. In fact, speaking about Christianity as if it is primarily about morality and being good, rather than being about Christ, also misses the point. Yes, Christianity does have a lot to say about morality (as do Lakoff and Johnson). Indeed, one of the central claims of Christianity is that we have all failed morally. But, the point of that claim is that our moral failure separates us from God. God is the goal of the Christian, not a moral life.

But it is understandable that Lakoff and Johnson would misunderstand what Christianity is really about. Many (perhaps most) people who call themselves Christians make the same error. It is particularly understandable given that they are writing in a North American context where ‘evangelicalism’ has become greatly mixed up with right-wing politics. In this view of things, developing ‘purity of heart’ is what matters, so it wouldn’t make all that much difference if God did not exist. The story and example of Jesus makes for a beautiful demonstration of a ‘good’ (moral) way to live. Unfortunately, to hold this view, one has to ignore a large amount of what Jesus says about himself in the four gospels.

The death of objective morality?

In another chapter of Philosophy in the Flesh, Lakoff and Johnson discuss conclusions after their critique of western philosophy. In one instance they make a point which I must disagree with:

[There is no] “Higher” Morality: Our concepts of what is moral, like all our other concepts, originate from the specific nature of human embodied experience. Our conceptions of morality cannot be objective or derive from a “higher source.”18

In one sense, this statement is correct. That is, our concepts of what is moral are based on human embodied experience. Therefore, whenever we think about morality, we are using metaphorical reasoning. Hence, we cannot claim that our moral reasoning directly reflects some objective, external source. But the implication of this statement is that, therefore, God is completely excluded from moral understanding. To put it another way: because I can explain that moral concepts come from embodied experiences, they cannot reflect an objective moral reality.

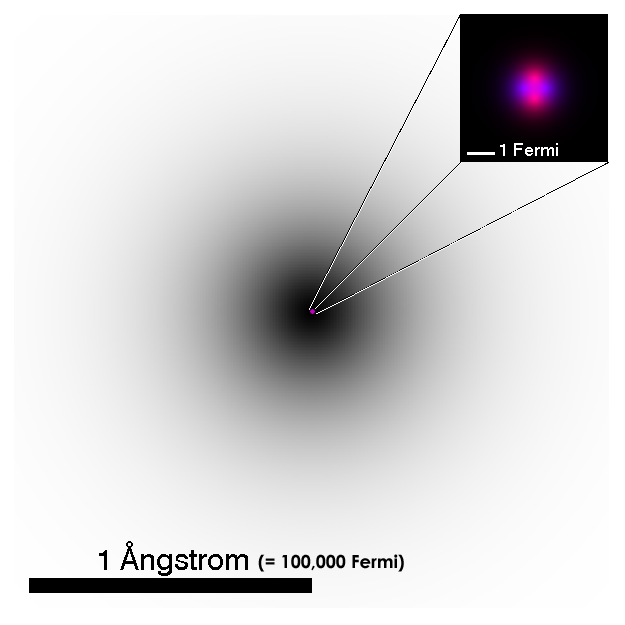

Perhaps this is not what Lakoff and Johnson intend, but it is certainly easy to read the statement that way. And the argument is flawed. Showing that we understand something metaphorically is not the same as showing that what we understand does not exist. By the same reasoning I can say that our understanding of atoms is based on metaphorical conceptions of balls and clouds (Figure 3.1). These are entirely based on embodied experiences—how atomic structure has been taught to us, and our experiences of balls and clouds. Our conceptions of atoms therefore cannot be objective or derive from ‘reality’.

Of course, the physicist will argue that there is more to atoms than the metaphors we use to conceptualise them. We have empirical evidence which gives us cause to believe that atoms exist and behave in certain ways. Similarly, Christians argue that understanding conceptual metaphors for morality does not necessarily mean that they have no higher source. We look to other evidence (primarily Jesus, and the documents about him in the bible) to examine our moral conceptions.

If God does exist, and he defines an objective moral reality, then understanding conceptual metaphor does imply that it is possible to have conceptions of morality that are wrong, or inaccurate. In fact, the bible argues that unless God intervenes, all our conceptions of morality are definitely warped from the reality he defines19. As Christians, we believe that Christ came to do something about that very problem.

Limitations of human reason

One thing that comes out of Lakoff and Johnson’s analysis, almost as an aside, is that there are limits to what we can know because our reasoning is metaphorically based. That is, because we experience the world entirely through our bodies, we cannot really understand things that cannot be conceptualised bodily. This is not to say that we cannot engage in any kind of abstract thought, but rather that our range of senses, and therefore our conceptual ability, is limited.

By its very nature, it is very difficult to give an example of this—how can I give an example of something I completely fail to comprehend? The nearest I can think is the example of a photon. According to Wikipedia, “the photon is the elementary particle responsible for electromagnetic phenomena”20—in particular, light21. We know that photons of light exhibit wave-like properties and particle-like properties at the same time. This is almost impossible to conceptualise because we do not experience anything like this through our bodily senses. Yet, these properties have been well documented. Even this is a poor example, however, since we can conceptualise both light and particles.

Applying this to street-level theology, this may be one of the reasons people find the doctrine of free-will versus predestination so confusing. In our conceptual models of causality, if something is predestined, choice does not exist, hence we do not have free will. The bible holds that we are morally responsible for our choice to accept or reject God. Yet, at the same time, it holds that God predestines some people for salvation (and, by implication, not others).

What is going on here? In western thinking, a primary metaphor we use to understand free will is freedom-of-motion. That is, freedom of motion implies a lack of physical constraints so that I can move wherever I wish. We map this bodily experience onto our concept of freedom-of-choice. If I am in gaol, then I do not have freedom because I cannot move about as I wish. I am constrained.

At the same time we also think of causes as physical forces. This is based on the bodily experience of achieving results by exerting forces on physical objects to move or change them. By coupling this metaphor with the freedom of motion metaphor, phrases such as ‘I had no choice—I was forced to go that way’ make sense. The phrase would make sense equally well if spoken by a prisoner, or of a man declaring bankruptcy. In the case of the bankrupt man, there is no actual physical force, nor is bankruptcy a literal direction of motion, but we understand these things metaphorically.

A common way to conceptualise predestination is as being forced to take a certain path (or paths) so that we arrive at a particular destination. The word ‘predestination’ even contains the metaphorical concept ‘destination’. So, if I am predestined, then my journey through life is constrained so that I reach a certain destination.

For myself, this conjures up images of train tracks. In Figure 3.2, a train travels from A to F. It does not matter which path the train takes (ABF, ADF, ACDF, ACEF), the destination is fixed. The tracks force the train to a certain destination.

It is difficult for us to conceptualise freedom and predestination in any other way. However, causes are not always physical forces and do not always work like physical forces. Neither does predestination, in the biblical sense, lead us to a physical location. Freedom of choice is not the same as freedom from physical constraint. Further compounding the problem is that we often hold a folk theory of single causes. That is, that there is a single actor that can be blamed for causing an event. The folk theory is easily demonstrated to be false. A common example is the question ‘Did slavery cause the American civil war?’. A yes or no will not suffice to answer it.

To give another example, imagine that I see a billboard advertising a particular soft drink. The advertisement appeals to me, so I then go and buy a bottle of the drink. Now, who is responsible for me buying the drink? Was it the advertiser? If I had not seen the billboard, then I would not have bought the drink. Yet, I still made the decision to buy the drink myself. The advertiser did not force me to do anything. Who is at fault? Both of us, and neither of us. Causality is not that simple.

It would be a mistake to extend the metaphor of advertisement to understanding predestination. God is not like the advertiser, and becoming a Christian is not like buying a bottle of soft drink. Yet the point remains that the metaphors we use to understand free-will and causality are limited. Our reasoning is limited by the metaphors that enable us to think about abstract concepts. Our minds are flexible enough to learn new metaphors, and thus broaden our capacity for understanding, but thinking will always be metaphorical.

The God who communicates

Another implication of the limitation of human reason is that there are things we simply cannot know about God. If God is transcendent, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, etc., then we will always have trouble understanding God’s perspective. We have no experience of what it is like to be omnipresent or omniscient, and we can only conceptualise them in terms of things we already know. Hence, like the mystics before us, we are forced to admit that such a God is beyond us: inconceivable; indescribable; unfathomable. How can embodied, finite beings ever hope to understand a God who is infinite spirit? Yet Christians believe that the transcendent, infinite God can, and does, communicate with us. We make a big deal out of the bible, because we believe that it is communication from God himself. God has made himself known through intelligible words and language. Leaving aside questions of how we got the bible in its current form, there are still difficulties. Communicating with someone in my own culture and environment is problematic enough. Most of the bible was written more than 2000 years ago in places and cultures completely alien from my own situation. Understanding a communication from a transcendent God, written by people in completely different cultures and times is always going to be a difficult job.

And when I read the bible myself, I find that it is difficult to understand… but not impossible. It helps to understand the culture and times in which the book was written. If I can understand how the people in those times and places thought, then I have a better chance of understanding the book I am reading. For example, I had no idea why the book of Revelation included this verse:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea existed no longer.

—Revelation 21:1 (HCSB), emphasis mine

The sea is beautiful, powerful, majestic. It speaks of God’s beauty, God’s power, God’s majesty. When I sit by the ocean and feel its amazing size and see the power of the waves, I am humbled and realise how small I am in comparison to the God who made the ocean. How could there be no sea in the new heaven and earth?

The phrase made no sense until I read a commentary. The commentary informed me that in Jewish thinking, the sea was symbolic of chaos and disorder. It was frightening and unpredictable. People died at sea. And the symbolism goes all the way back to the creation story:

Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness covered the surface of the watery depths, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the surface of the waters.

—Genesis 1:2 (HCSB)

When God created the universe, he spoke into the chaos and darkness, bringing order and light. I now understand that when it says ‘the sea existed no longer’, it is indicating that creation has reached fulfilment and chaos and darkness have been eliminated.

The upshot is that understanding communication across 2000+ years will require hard work. But surely if this communication really is from God, it is worth the effort. If we received a message from outer-space indicating that alien life existed, then I imagine we would spare no amount of effort to decode it and understand it. It would be worth the effort to find out what people from another world had to say. How much more important should it be when the creator of the universe sends us a message?

An embodied God?

If understanding the bible is made difficult because of temporal, geographic and cultural differences, it becomes even more difficult when I try and understand things from the perspective of a transcendent God—one who has always existed, is everywhere, knows everything, and is all powerful. We said earlier that all humans have a couple of things in common: a body and a brain. The Almighty is spirit. Spirits, by definition, don’t have bodies. They don’t inhabit the world of matter. How then can we hope to understand him?

Of course, Christians believe that, in Jesus, God became a man with a body and experienced real, bodily experiences. This is one thing which differentiates Christianity from most other religions. God didn’t just make himself look like a man for a little while in order to have sex with a particularly pretty female who took his fancy—no, he was born to a real mother, and lived as a real human being. He lived the whole thing as one of us—birth to death, and then some.

…Christ Jesus, who, existing in the form of God, did not consider equality with God as something to be used for His own advantage. Instead He emptied Himself by assuming the form of a slave, taking on the likeness of men. And when He had come as a man in His external form, He humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death—even to death on a cross.

—Philippians 2:5—8 (HCSB)

Because of Jesus, God himself knows, from personal experience, what it is like to have a human body. He knows what it is to only be able to see in one direction; to have eyeballs and ears and to feel hungry. But it also works the other way. In Jesus, God did more than answer the ‘what if God was one of us?’ question. In Jesus, God shows us what he is like in a way that we can understand.

Long ago God spoke to the fathers by the prophets at different times and in different ways. In these last days, He has spoken to us by [His] Son, whom He has appointed heir of all things and through whom He made the universe. He is the radiance of His glory, the exact expression of His nature, and He sustains all things by His powerful word. After making purification for sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high.

—Hebrews 1:1—3 (HCSB)

“God, the blessed and only Ruler, the King of kings and Lord of lords, who alone is immortal and who lives in unapproachable light, whom no one has seen or can see”22—this God has made himself known by becoming a human being. In Christ we see the visible image of the invisible God.23

So, God himself answered the question of how a transcendent, spiritual God could communicate about himself to finite, embodied mortals. The immortal took on mortal flesh and showed himself to us. We can know God because he has made himself known. It may still be difficult, but so is learning to speak another language. Surely learning to see things God’s way takes even more of a mental shift, but is much, much more rewarding in the end.