What’s the point of art?

I have a suspicion. I dare not even call it a hypothesis, let alone a theory. My suspicion is that art has a purpose. A bigger, grander purpose than we assume. A purpose we’ve kind-of suspected all along. But one that’s difficult to articulate; hard to pin down.

What is art for? What is the point of it? It’s not like food, clothing and shelter. We don’t die without art. At least, not straight away. Take away air, or water, or food, and we die. But we seem to be able to last much longer without art. Art doesn’t appear to be essential for life. In fact, it even seems frivolous at times. Its utility is not obvious. Yet, we humans keep making it. And the better our physical needs are met, the more art we seem to make.

And what business do Christians have with art? We seem fine with ‘worship’ songs and hymns. But churches are no longer the great patrons of art they once were, long ago. In fact, we seem to have become suspicious of art. Particularly in the western protestant sub-culture I grew up in. It seems impractical. We’re supposed to be looking after widows and orphans. We’re supposed to be proclaiming the good news. What good is art to a man dying of starvation? Can you feed him a painting? Will interpretive dance find the homeless woman a safe place to sleep? Is art a waste of time?

Defining Art

And what do I even mean by ‘art’? For this discussion, I want to talk about two definitions of art:

- Art as the creation of original cultural goods. This is a broad definition. It includes things like paintings and plays and musical performances. But it also includes things like the design of the iPhone. Or a particularly well-written piece of code. Or that special pizza recipe you invented. It could be a website, or a journal article, or a flower arrangement. I will refer to art by this definition as lowercase-a ‘art.’

- The Arts, capital A. This is a narrower definition. And it hems in most of the things we associate with art. That is, paintings, sculpture, theatre, musical performances, dance and poetry. And I would also include novels and movies here too.

In some ways, the broad (lowercase-a) definition is easier to talk about. We all like innovation and creativity. It’s easy to argue that creativity makes the world a better place. Innovation solves problems. Small-a art dovetails in with the innovation story. We solve problems by creating original cultural goods. The purpose of small-a art is almost self-evident. But what about the narrow definition—Art with a capital A? What’s the point of it? Does it have a purpose we can point to and say ‘this is good’?

In the past few decades, some have tried to dodge the question altogether. Art is for Art’s sake. Art is good because it is art. Or so the argument goes. And I understand where this comes from. We feel that Art is good. But it’s hard to explain why. We fear that by trying to define Art’s purpose, we cheapen it. It somehow becomes less noble. Declaring Art for Art’s sake keeps the mystery. But this is a cop-out. We’re afraid to ask the question of Art’s purpose. We worry that we’ll discover Art has no purpose. If we look too close, we’ll have to wake up and smell the disenchantment. And if it has no purpose, then why bother funding it? But I want to ask the question anyway. I think there are good answers to be found. So then… What is the purpose of Art?

What makes good Art?

One way to approach the question is to consider ‘what makes good Art’? How do we measure it? I am only speculating, but my intuition says we tend to measure Art by the strength of emotion it evokes in the viewer.1 That is, the stronger the emotion the artwork arouses, the ‘better’ it is. Note, the emotion may not always be a positive one. It’s the strength of the emotion that matters, not how positive it is. And, as far as it goes, this measure isn’t bad. But emotions, by definition, are subjective. One piece of Art might produce a stronger emotional response in me than it does for you. So the simple measure only allows us to say that an artwork is ‘good’ for me or for you. But can we say that one artwork is, in general, better than another?

One way would be to ask, does this produce an emotional response for most of its intended audience? And do the responses reflect what the artist intended? This then allows us to talk about craft. That is, the level of skill that goes into creating a work of Art. An artist with more skill will have a greater ability to translate their ideas into an artwork. And some of these ideas will resonate more than others. So, a ‘good’ piece of Art will more often produce emotional responses in the intended audience. And ‘bad’ Art will produce (intended) strong emotional responses less often. A good artist, because of their skill, can produce good Art more often than a less skilled artist.

Does this get us any further though? We’ve moved from “Art for Art’s sake” to “Art for emotion’s sake.” But emotion isn’t much of an end in itself. Emotions are definitely a part of what makes us human. We’ve made countless science fiction movies on that theme.2 But they’re still not an end unto themselves. We don’t have to look far for examples of emotions getting in the way of our ‘better’ judgement. So, what have we got? Good Art evokes emotion, but emotion is not a purpose in itself. What then, is the purpose of Art?

Experiencing truth

Here is my proposal: The purpose of Art is to evoke feelings so that we experience truth. My hypothesis is that Art ought to point to something other than itself. It may be something abstract, like the concept of ‘home’. Or it may be something concrete, like a particular landscape at dusk. But either way, it exists to let us experience truth.

To clarify, let’s compare an artwork to a scientific paper3. A scientific paper attempts to make its findings as clear and persuasive as possible. It does this by detailing experimental methods—how the author achieved the results. And the paper refers to other scientific papers to show that the author has done their homework (so to speak). It says, in essence, three things:

- We (the authors) have read what other people in this field are doing;

- Seeing a (possible) gap, we ran this set of experiments;

- Based on the results we conclude that these things are true…

The paper is precise and constrained in what it asserts. But the precision and transparency are all in the service of persuading you of an argument.

Compare this to an artwork. Instead of presenting arguments, it assails your senses. George MacDonald put it this way:

If a writer’s aim be logical conviction, he must spare no logical pains, not merely to be understood, but to escape being misunderstood; where his object is to move by suggestion, to cause to imagine, then let him assail the soul of his reader as the wind assails an aeolian harp. If there be music in my reader, I would gladly wake it.4

Art aims to ‘move by suggestion’, rather than by argument. It ‘wakes’ something inside us. It digs up memories and associations. We read a poem, and we can smell fresh-cut grass and the neighbour’s burning rubbish. We watch a movie and we cry when Old Yeller has to be put down. We view a painting, and something about it makes us feel tight in the chest. Art deals in sensations and experiences. So, in one sense, it has a broader range of communication than the scientific paper. But as a consequence, it is much less precise. The artist has much less control over how the viewer perceives their work. Yet the artist has the freedom to communicate much more than the scientist.

This point is important. Because there is a difference between knowing something and experiencing something. Jonathan Edward wrote about this in his sermon A Divine and Supernatural Light:

There is a difference between having a rational judgment that honey is sweet, and having a sense of its sweetness. A man may have the former, that knows not how honey tastes; but a man cannot have the latter unless he has an idea of the taste of honey in his mind. So there is a difference between believing that a person is beautiful, and having a sense of his beauty. The former may be obtained by hearsay, but the latter only by seeing the countenance. There is a wide difference between mere speculative rational judging any thing to be excellent, and having a sense of its sweetness and beauty. The former rests only in the head, speculation only is concerned in it; but the heart is concerned in the latter. When the heart is sensible of the beauty and amiableness of a thing, it necessarily feels pleasure in the apprehension. It is implied in a person’s being heartily sensible of the loveliness of a thing, that the idea of it is sweet and pleasant to his soul; which is a far different thing from having a rational opinion that it is excellent.5

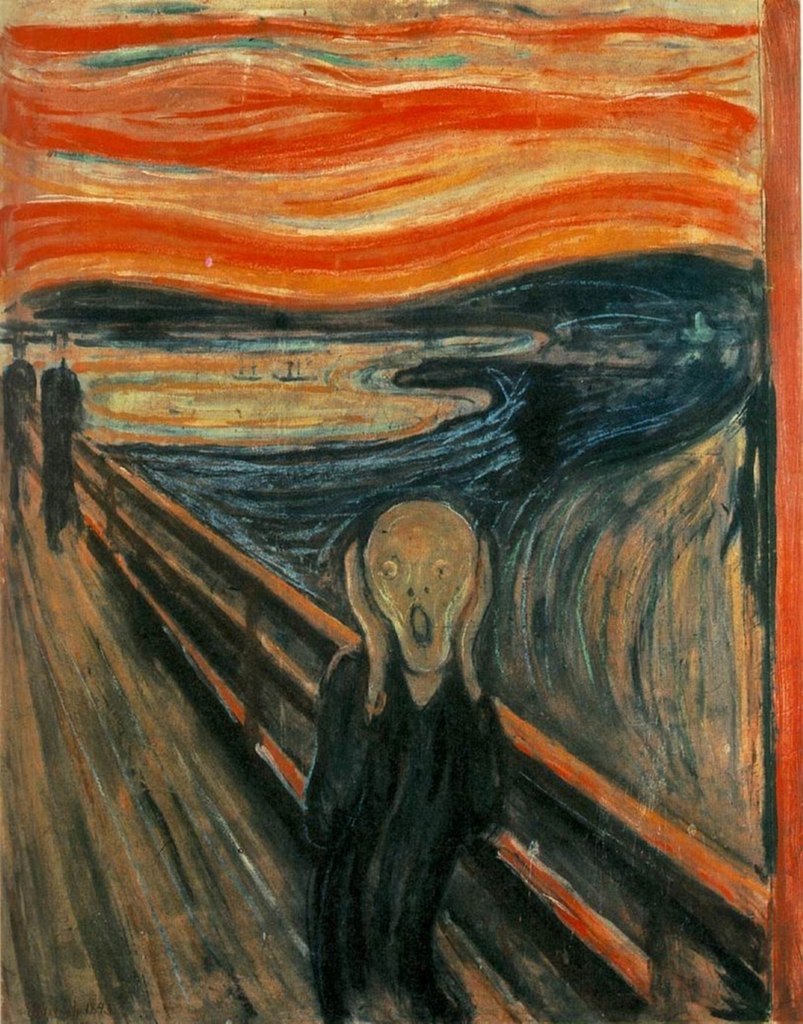

We could, for example, take a survey. Our survey might conclude that 99 out of 100 people agree that anxiety is unpleasant. We could even ask them to describe what symptoms they experience with anxiety. From this, we might conclude that anxiety is generally considered unpleasant. And we might also conclude that people often feel tightness of chest, trembling, or lack of energy. But Munch’s The Scream gives you a sense of what it feels like to experience anxiety.

Through art we don’t just understand; we feel. We experience. Art moves us in ways that can bypass the walls we build to keep out the truth.6

What truth?

Okay then, Art is about experiencing things. But experiencing what? If the purpose of Art is to assist us in experiencing truth, what truth are we talking about? Or whose truth?

Let’s leave the question of epistemology aside for the moment. Let’s assume that it is possible to know things. Even so, different groups of people often disagree on truth. Is there a God? If there is, what is this God like? What is wrong with the world (if anything)? What would make the world a better place? How we answer these questions has a profound impact on what we consider to be truthful. And large implications for what we think Art is for.

What if we assume that there is no God? If there is no God, then our aesthetic sensibilities have no real meaning. They are nothing more than neurological leftovers. After all, what is going on when we view Art? Neurones are firing. Our brain is one giant association-making machine. And as we view Art it’s matching what we see with other things that we’ve seen (or heard or smelled). In the process, other neurological ‘circuits’ fire as we recall past experiences. Some of those circuits might trigger hormonal responses, and we experience emotions. But with Art (if there is no God), these responses are responding to a fake. Our brain is mis-firing—so to speak. Art is nothing but an interesting byproduct of our brain’s wiring.

That is not to say that Art can’t have any purpose. But it has to be one that we invent ourselves. Alain de Botton and John Armstrong consider this in their book Art as Therapy. They argue that Art can have a noble purpose as a psychological tool. It can help us consider our own humanity.

What, then, are the consequences of holding to a therapeutic vision of art? Principally, the conviction that the main point of engaging with art is to help us lead better lives—to access better versions of ourselves. If art has such a power, it is because it is a tool that can correct or compensate for a range of psychological frailties.7

This is not a bad thing. Yet because of their assumptions, there can be nothing transcendent about Art. They conclude their book by suggesting that ‘the true aspiration of art should be to reduce the need for it.’ That is, ‘having imbibed the ideals that art displays, we should fight to attain in reality the things art merely symbolises.’ 8 And I applaud the sentiment. This is a noble cause. Yet, if we assume there is no God, Art can never give us anything more than reflections of ourselves. Those reflections might be flattering distortions that point to ‘better versions of ourselves.’ Or they might show us disturbing reflections of our moral ugliness. But nonetheless, still only reflections.

But what if there is a God?

I am a Christian writer. So pause with me for a moment. What do you think will come next? What do you expect my argument to be? Is it ‘be a good boy or girl and you get to finger-paint with Jesus in heaven when you die’? Or that Christians have something great to make Art about? Or are you expecting me to assert that Christians have the true truth because it’s true? And all you have to do is believe that true truth—so let’s make Art for Jesus!? I’m serious. What would you expect me to say? Tweet me and let me know.

There is so much I could say. But I want to return to some of the questions I asked at the start. How could a Christian justify making Art when we’re supposed to be helping widows and orphans? How can Art help a homeless woman find somewhere safe to sleep? My answer would be that Art cannot do that. But it could help me want to help the homeless woman. Art can help me see that she is made in the image of God. It can help show me that she has worth and dignity that would otherwise be invisible. Art can help remind me of the God who became like her—homeless, poor and outcast. And once she has shelter and food, it can help her understand that she has dignity and worth. It can help give her hope and purpose.

Art cannot do all that on its own though. I do not want to claim too much for Art. We still need to feed the hungry. We still need to help those widows and orphans. There are no excuses. And we still need to speak the truth. The bible is clear on that point. But Art can help. It is one thing to know I ought to help widows and orphans. It is another thing to be moved to act. That is where Art comes in.

Propaganda

But, this is starting to sound a lot like manipulation. Is Art only a tool to make me feel like doing things I otherwise wouldn’t? Is Art no more than a nice label for propaganda? As George Orwell wrote in 1941:

[The 1930s] reminded us that propaganda in some form or other lurks in every book, that every work of art has a meaning and a purpose—a political, social and religious purpose—that our aesthetic judgements are always coloured by our prejudices and beliefs. It debunked art for art’s sake.9

And Upton Sinclair wrote in his self-published book Mammonart, in 1925:

All art is propaganda. It is universally and inescapably propaganda; sometimes unconsciously, but often deliberately, propaganda.10

If we claim that Art is for experiencing truth, then we cannot claim there is no element of persuasion to Art. And hence Art can be used as propaganda—as indeed it has. But calling Art propaganda is the same as saying ‘Art is a form of communication’. But it doesn’t sound so pithy. As Botton and Armstrong say, Art is a tool. And that tool can be used for noble purposes or ignoble.

Art is made by artists. And artists are people. People bring their social backgrounds and assumptions and political views into their Art. Art is always partly a reflection of the artist. But, even if Art is no more than a tool, Botton and Armstrong argue that Art can still point to something ‘higher’. Even if that something higher is only a ‘better version of ourselves’. But what if there is a God? What difference does that make?

What if…?

Let me ask then, what if? What if there is more to this universe than meets the eye? What if aesthetics are more than neurological noise? What if beauty and transcendence are more than personal preferences? What if love is real? What if this tragic story could have a happy ending? What difference would that make to the purpose of Art?

What if Art could point to something beyond this material world? What if it could be a keyhole through which we glimpse the eternal? What if it could help make the unseen, seen? What if Art could give us glimpses of the unknowable?

One way to use Art is to help make the truth we know in our heads sink into our hearts. It could help truth become part of our lived experience. This is a good idea. But it’s not so very different from Art as therapy—helping us become better versions of ourselves. There is more to what Christians believe than self-improvement though. And self-improvement doesn’t answer those grand questions above. I said earlier that I suspect that the purpose of Art is to help us experience truth. But what do Christians believe is the truth?

In contrast to what many think, the truth of Christianity is not a set of doctrines you need to get right in your head. (Though we do have doctrines). Nor is it a set of rules to obey. (Though we have some of those too, just not as many as you might assume). No, Christians believe that the truth is a person. Jesus said:

I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me. 11

It sounds a bit exclusive. Unless it’s… ahem, true. But if the truth of Christianity is a person, then the core of Christianity isn’t the doctrines or laws. No, it’s a relationship.

This sounds weird on first hearing. I think there are two reasons for this:

- Because it’s different. We’re used to thinking about truth as precise things, like equations and axioms. Things we can draw clear boundaries around. Talking about truth as a person sounds… fluffy; primitive; the result of lazy thinking. But that’s because it’s unfamiliar, not because it’s implausible.

- When we state that the truth is a person, we tend to assume that means the truth is somehow smaller. We mentally insert ‘just’ into ‘truth is a person,’ so it becomes ‘truth is just a person’. As if somehow a person is less than an equation or an axiom. As if people are somehow less intricate or less interesting than laws or axioms or equations or logic or doctrine.

We’re trained from youth to think of truth as the correct answer to a question. Or a statement we can verify as fact. But if you think about it, a person is much more than a statement, or the correct answer to a question. For example, consider my relationship with my wife. I can know all kinds of facts about her. She is female. She is shorter than I am. Knowing these facts and getting them right is helpful and important. But there is so much more to her than these facts.

Knowing my wife as a person only happens in the context of a relationship. I will spend the rest of my life getting to know her. Sometimes it might be helpful to memorise facts about my wife. Like her birthday, or her favourite perfume. I could even write some of these facts down in the form of statements. But the statements are not her. She is so much more than I could ever write down. I could never summarise her down to a set of facts or rules. In the same way, if we say that the truth is a person, that makes the truth more, not less than something like an equation. The truth is bigger and more complex than we like to think.

But what does that mean for Art? I’m arguing that the purpose of Art is to help us experience truth. If Jesus is the truth, does this mean Christians should make endless pictures of Jesus then? Does every painting have to have a cross in it? Should every song mention his name? The answer is no. But why?

We’ve established that the truth being a person makes the truth bigger, not smaller. If we made every painting a religious icon, then we would be making the truth small again. If Jesus is the truth, then that includes everything true. The truth includes physics and mathematics and biology. It includes sunsets and mountains and what it feels like to be part of a family. We don’t make every sculpture a crucifix because that’s only one part of the truth. A crucial part yes, but not the entirety of truth.

Besides, icons can get in the way of experiencing truth. We humans have a bad habit of substituting the picture for the real thing. Real truth is much broader and more subtle than the icon can convey. Real truth includes all life’s complexities and intricacies. It’s bigger than the Art forms we adopt for use in religious practices. That’s why we need more than just religious Art.

If Jesus is the truth, then the truth is much bigger and more complicated than we like to think. This doesn’t mean that we abandon the facts and doctrines. To use the analogy of my marriage again, it is important that I remember my wife’s birthday. Not to get it right for the sake of accuracy, but because it has consequences for the relationship. So too with Jesus. It’s essential we get our doctrines right and obey what he commands. But the truth is bigger than the laws and doctrines. And Art can help us remember that.

Now, none of this is an argument for why you should believe that Christianity is true. You should believe Christianity because there is strong evidence for it. Others have done a much better job of explaining that evidence than I could. But, if you investigate Christianity and don’t wish it were true, then I can think of only two explanations:

- We’ve done a poor job of explaining it; and/or

- You haven’t understood it.

Either way, further investigation is warranted.

But getting back to Art. My suspicion is that the purpose of Art is to help us experience truth. This means that what you believe to be truth has a massive impact on what you think about Art. And Christians believe that truth is a person, Jesus. This doesn’t mean that all Art must be portraits of Jesus. But it does mean that truth is deeper and more complex than we tend to think. This doesn’t mean that we abandon doctrine or laws. Far from it. But it does mean that Art can be helpful in broadening our understanding of truth.

…art offers us fresh perspective. It provokes us to think, and it challenges us with hard questions and uncomfortable realities. It teaches us how to pay attention to the beauty and wonder around us, arousing us from the stupor of everyday life to appreciate the signs of glory all around. Great art can make the past tangible to us through realistic portrayal, or give us vision to gaze into possible futures. Sometimes it breaks our heart; other times it heals it. It can lift us out of weariness, isolation, or sadness. Great art can transform us.12

This brings me to my final thought, which is that if:

- The purpose of Art is to experience truth; and

- Truth is a person—Jesus; and

- Truth is bigger than doctrines and laws; and

- Art can be helpful in broadening our understanding of truth;

Then, we need to take care with our Art. At least as much care as we do making sure that we get our doctrines and laws right. Even more so, given the lack of precision in Art. I come from a Reformed-flavoured evangelical tradition. And we tend to be passionate about defending doctrine. We mount arguments and try to defend those beliefs that we hold dear. We send our pastors to get rigorous academic and theological training to that end. But if my suspicion is true, then we need also need Christian artists to be making Art. And they need to be skilled artists. More importantly, we need artists who know Jesus to be making Art.

If you are a Christian who makes art (big or little A), we need you. We need you to:

- Know Jesus. If the purpose of Art is to help us experience truth, and Jesus is truth, then knowing Jesus matters. The deeper you know Jesus then the more depth there will be to your art. It will have a connection to something richer and full of life than it could otherwise. We need your art to help us experience Jesus. To do that, we need you to know him well.

- Get skilled. Knowing Jesus isn’t an excuse to make poor quality art. No, it makes it all the more important that it be the best art we can make. And if you are not particularly skilled, then the only way to get skilled is to make more Art.

So please, make more art. Even if you don’t ‘do’ art, consider that those artists might be doing something important. Whether you are a Christian or not, art is important. And if you are a Christian, we have something big to be making art about.

If you read this far, you might be interested in some other things I’ve written: